Katsushika Hokusai

(Edo 1760 - 1849 Edo)

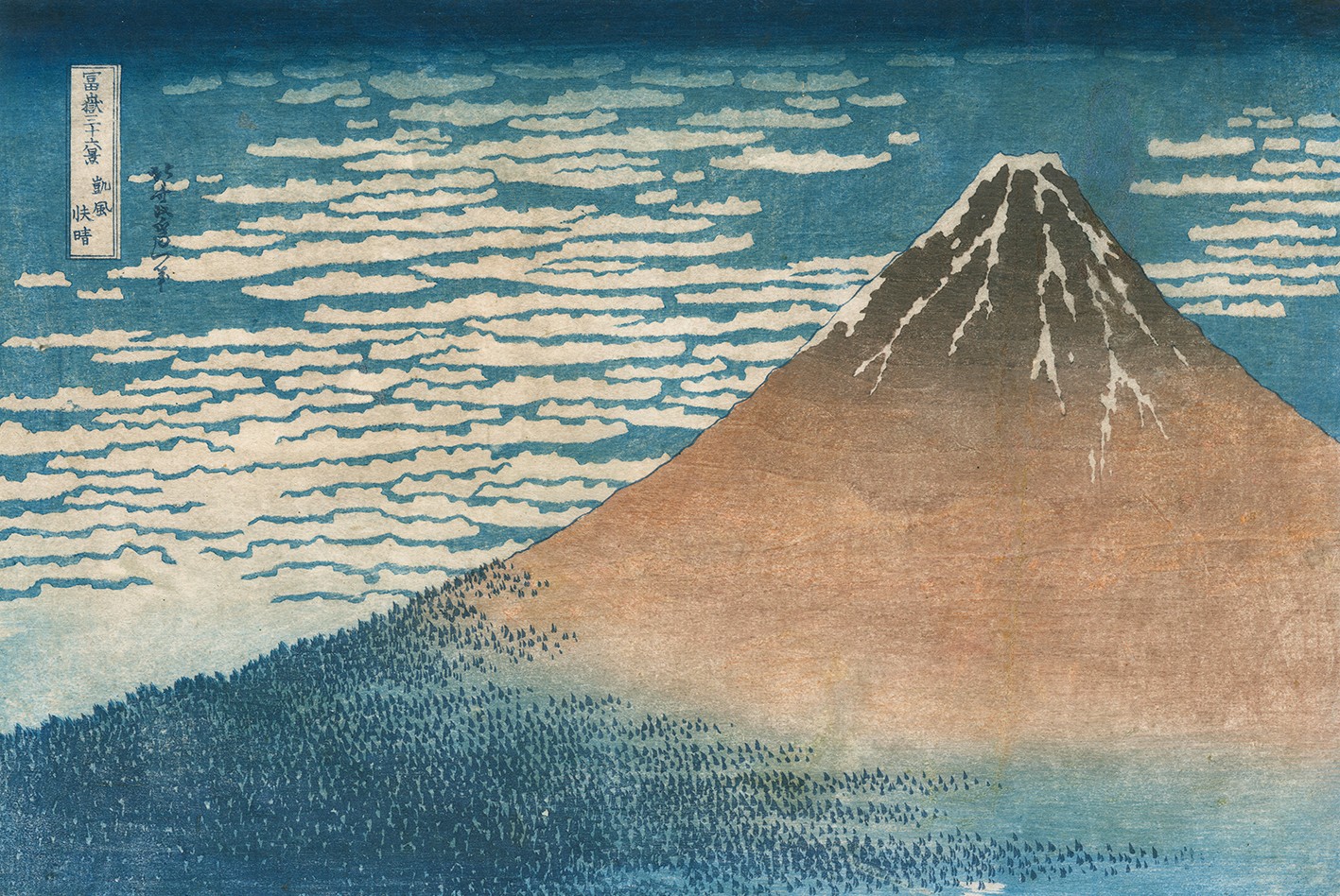

Gaifu kaisei, The Red Fuji, (Fresh Wind from the South on a Clear Morning), c. 1830-1832

Colour woodcut, 25,5 x 37,6 cm (10.04 x 14.80 inches)

Katsushika Hokusai

(Edo 1760 - 1849 Edo)

Gaifu kaisei, The Red Fuji, (Fresh Wind from the South on a Clear Morning), c. 1830-1832

Colour woodcut, 25,5 x 37,6 cm (10.04 x 14.80 inches)

Re: 827

Provenance: Private collection

Description:Nishiki-e Colour woodcut, signed in the plate: Hokusai aratame Iitsu hitsu

Series: Fugaku sanju rokkei (The thirty-six views of Mount Fuji - first series)

Date: 1830–2

Format: oban yoko-e (255 x 376 mm.)

Publisher: Eijudo (missing)

Censor: kiwame (missing)

Literature

Forrer 88.107.1

Lane 288.141.2

Forrer&Goncourt, 264.8

Hokusai Museum II.24

Calza V.35.2

Exhibited

Hokusai (Edo 1760 - 1849). I capolavori, ed. S. Salamon, exhibition catalogue,

Turin 2005, no. 2

A superb and extremely rare proof with brilliant colours, in the first edition of two, with the key block inked in “Berlin blue”, a characteristic of the first edition in the first series. Impressed on Japanese paper which can be dated to the first half of the 19th century. In perfect condition, aside from an exceptionally skilfully executed restoration in the sky top right. Complete with engraved part and with a very slender margin visible in places on the lower edge, an extremely rare feature in Hokusai’s prints

The profile of Mount Fuji stands out majestically against the backdrop of a blue sky, albeit a sky marked with rows of ‘herringbone’ (‘iwahigumo’) clouds which were to become a typical feature of Japanese art. The light, coming from the southeast, tells us that it is very early in the morning, while the tiny trees at the foot of the slope appear to be swaying in a breeze that compresses their branches, giving them the appearance of slender triangles.

‘Gaifû kaisei’ – Literally ‘Sweet breeze, clear morning’ – was the most celebrated icon in Japanese art and culture for almost two centuries. On a par with The Great Wave off Kanagawa, this is Katsushika Hokusai’s best-known work, a manifesto of his mature style and, on a more general level, of his Iitsu period – after the name that he took at the age of sixty to indicate the conclusion of one life cycle and the start of another (‘Iitsu’simply means “another”). But while The Great Wave bolstered his reputation primarily in the West on account of its poetic affinity with the Romantic and post-Romantic view of nature in Europe and the United States, the Red Fuji instantly became a symbolic image of the Japanese nation, chiefly on account of the mystic value that the Japanese people attach to the mass of the volcano with its perpetually snow-covered peak.

Mount Fuji, which last erupted in 1708, has been an object of fear, deference and veneration for the Shintoist faith since time immemorial. The celestial manifestation of its peak, Konohanasakuya-hime, in the mythology and collections of poems from the Heian period (8th – 12th century) takes the shape of a ravishingly beautiful princess, the daughter of the god of the mountain and bride of heaven, the patron of fishermen and of women with child, and the goddess in her own right of fishing, farming and weaving. Thus for Shintoists the peak of Fuji protects and rules over Japan and its flourishing commercial and industrial activities. At the same time, starting in the 12th century, Buddhist monks also began to fill the slopes of the mountain with sanctuaries, and the climb to the top of the mountain became a traditional pilgrimage of purification and rebirth. Thus contemplating the volcano’s profile is a sacred moment bringing together different traditions and cultures and representing a spirit of continuity in Japanese history. The climb to the top is also a perpetual symbol of man’s relationship with nature, the pole star (‘Hokushinsai’ in Japanese, the abbreviated form of which is ‘Hokusai’) on a constant journey of rebirth that follows the rhythm of the day – thus of the light – and of the seasons[i].

Katsushika Hokusai was born in Edo (the traditional name of the city of Tokyo, used until 1867) in the second half of the 18th century[ii]. After training with a carver of printing plates from the age of fourteen, he entered the workshop of the great painter Katsukawa Shunsho (1726–93), an expontent of the style known as ‘Ukiyo-e’ (literally ‘picture of the floating world’) and a populariser of prints devoted chiefly to actors of the Kabuki theatre. On his master’s death, Hokusai, who signed himself ‘Sori’ at the time and was just over thirty years old, became the master of a school in his turn, his style of portraiture drawing closer to that of Kitawaga Utamaro and shaking off the stiff, simplified settings found in Shunso’s work. The growing success of Hokusai’s compositions, admired even by dignitaries at the imperial court, did not deter him from practising popular illustration, producing the “yomi-hom” (“reading books”) that were such favourites with a large swathe of the population and were snapped up for a song throughout the country. From 1820 – the year of his rebirth at the end of the astrological cycle in which he had spent the first sixty years of his earthly existence – animals and the landscape became the preferred theme of his prints. He himself appears to have been aware of the importance of this change when he wrote his best-known poetic testament in the postface to One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji in 1835: “From the age of six I had a penchant for copying the forms of things, and from about fifty, my pictures were frequently published; but until the age of seventy, nothing that I drew was worthy of notice. At seventy-three years, I was somewhat able to fathom the growth of plants and trees, and the structure of birds, animals, insects, and fish. Thus when I reach eighty years, I hope to have made increasing progress, and at ninety to see further into the underlying principles of things, so that at one hundred years I will have achieved a divine state in my art, and at one hundred and ten, every dot and every stroke will be as though alive. Those of you who live long enough, bear witness that these words of mine prove not false. Told by Gakyo Rojin Manji, Old Man Mad About Painting”[iii]. Thus in Hokusai’s view the crucial moment in acquiring the means to paint lies in dialogue with natural elements and subjects: animals, plants, trees, waves as tall as mountain tops and, finally, the light on the slope of Mount Fuji. And indeed it is no mere coincidence that this realisation should have dawned on him immediately after he published his Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, by far the most popular and best-known series of his entire career. The book comprises 46 polychrome woodcuts published between 1830 and 1833 by Nishimuraya Yohachi, a publishing house that had been publishing the great Ukiyo-e artists’ illustrations for almost a century. In view of the edition’s success, the first thirty-six prints were followed by another ten in which the central role played by natural elements diminishes and the human component is once again thrust to the fore. In the thirty-six views in the original edition, on the other hand, the work’s poetic raison d'être emerges quite clearly: it is a kind of admirative description of the Japanese people’s daily lives scanned by the rhythm of the colours and light, and protected by the reassuring snow-capped peak. In the first woodcut in the series, the triangle of Mount Fuji sits in the centre, an unyielding bulwark against the storms of life, at the very moment the Great Wave breaks over the boats that are fated to go under. Nor does it come as a surprise that the second woodcut is the very work under discussion here, the image of an eternal, comforting spring depicted in the morning with glimpses of blue sky and a light breeze, responding to the icy winter and the storm of the Great Wave. The clouds have a particular significance here, their shape having most likely been inspired by the impressions that Hokusai had built up by studying 17th century Dutch etchings and which he transmitted in his turn to Japanese artists of later generations – a shape that prompted Timothy Clark[iv] to liken them to a school of fish teeming in the blue of the sea.

But while contact with the tradition of Dutch art undoubtedly played a central role in Hokusai’s development, the contribution that this genial Japanese engraver left as his legacy to 19th and 20th century European art was even more momentous. The opinion voiced by that great historian of Japanese art Richard Douglas Lane, referring incidentally to this very work, is well-known: “We can confidently state that in Red Fuji we can trace the seeds of Impressionism, of Post-Impressionism and of Abstract Art, in fact the seeds of much of what is ‘modern’ in modern art”[v]. But while scholars have often highlighted the link between Hokusai and the art of Monet, Gauguin, Van Gogh and the abstract artist Kandinsky, they have far more rarely associated him with the style of the Fauves or the Die Brücke and Blaue Reiter movements. Yet precisely the strong contrast of the primary colours in Red Fuji point not only to the Impressionists’ study of light but also to the animated nature of early Expressionist landscapes. In a nutshell, the various paths pursued by European art share a common and luminous source in this brilliant composition.

The exemplar under discussion in this short essay was published in the first edition of the series (1830-3) and is remarkable for its excellent condition. Identical dimensions and the presence of the slender margin – which can be seen in this instance on the lower edge – associate this woodcut to a better-known work in the collections of the British Museum (inv. 1906, 1220, 0.525) which has been shown at international exhibitions devoted to Hokusai on more than one occasion[vi].

[i] For the importance and significance of Mount Fuji in Japanese tradition and art down the ages see C. Uhlenbeck, M. Molenaar, Mount Fuji. Sacred Mountain of Japan, New York 2000.

[ii] For Hokusai’s artistic career see: Hokusai. Il vecchio pazzo per la pittura, ed. G. C. Calza, exhibition catalogue, Milan 1999.